"Jimmy Carter's Jewish Problem"

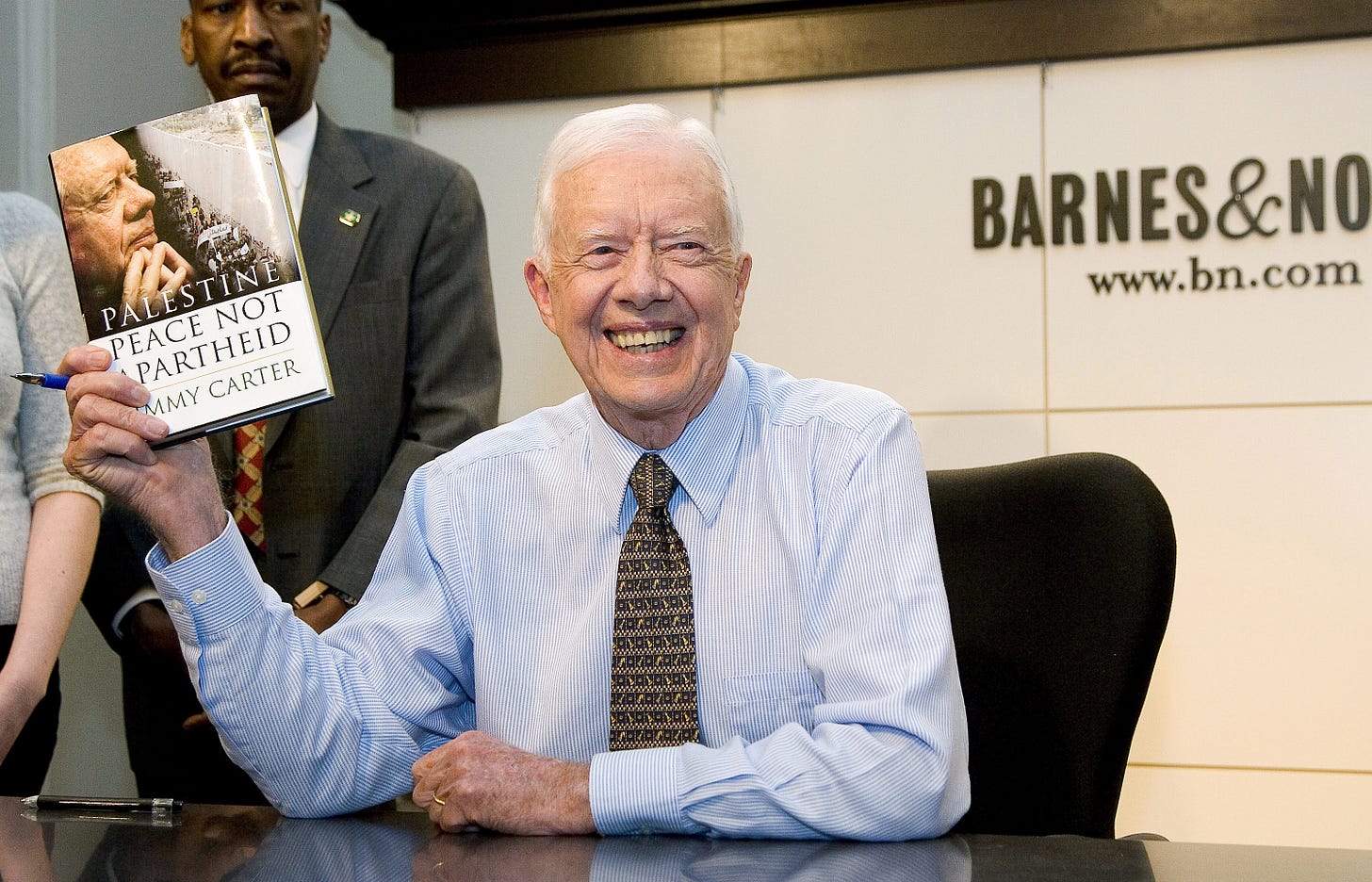

Perhaps the most interesting tidbit from Jimmy Carter’s state funeral last week came somewhat counter-intuitively from Gerald Ford. Ford had agreed to produce a preemptive eulogy for Carter around 20 years ago, just as Carter had delivered a eulogy for Ford when he died in 2006. Ford’s son delivered the eulogy on his father’s behalf. It was a bit like a public opening of a time capsule, and therefore inherently intriguing to any student of presidential history. Ford and Carter became close friends after they rode together on Air Force One to the funeral of Anwar Sadat, the Egyptian president with whom Carter had brokered the Camp David Accords in 1978, only for Sadat to be assassinated a few years later, probably by Islamist malcontents who reviled Sadat’s accommodation with the US and Israel. In the eulogy, Ford wrote of he and Carter resolving to jointly “confront the Palestinian issue directly.” According to Ford’s son, his father had continuously updated the eulogy over the years, and it’s plausible that the final updates came around the time that Carter’s book, Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid, was published in November 2006. Ford died about a month later.

A furious uproar ensued upon the book’s release. One notable contribution was from Deborah Lipstadt, the court historian later appointed to the Biden Administration as “special envoy” for combating anti-Semitism — a makework State Department post whose vague requirements mostly seem to entail exhorting corporations and supplicant governments to more aggressively monitor and punish unseemly political speech. Lipstadt’s January 2007 column in the Washington Post, obnoxiously titled “Jimmy Carter’s Jewish Problem,” strikes a contrived tone of bereaved disappointment that Lipstadt had tragically found herself needing to accuse the once-beloved Carter of trafficking in “anti-Semitic stereotypes.” The column culminates in a predictably idiotic comparison of Carter with David Duke. Typical for Lipstadt, her charges of “anti-Semitism” more rely on elliptical imputations of “anti-Semitism” by omission or convoluted inference, rather than anything plausibly “anti-Semitic” that Carter had ever actually done or said. Conspicuously few direct quotes from Carter’s book supply the ammunition for her fusillade. Instead, Lipstadt complains that Carter only “makes two fleeting references to the Holocaust” in a book focused on the political and diplomatic situation of Palestinians, which is enough to get Lipstadt’s darkest suspicions roused. Carter’s failure to dedicate his book more robustly to the Holocaust “gives inadvertent comfort to those who deny its importance or even its historical reality,” according to Lipstadt. That Carter had once signed the legislation that brought the US Holocaust Museum into existence was no solace, per Lipstadt.

Having finally read the book myself last year, Lipstadt’s charges, and the wider uproar, look all the more preposterous in retrospect. It’s a very restrained and cautious book, although admittedly radical by the standards of ex-presidents. Today, Carter’s comments read almost like consensus banalities. Identifying the principal roadblocks to a regional settlement, Carter writes: “Some Israelis believe they have the right to confiscate and colonize Arab land and try to justify the sustained subjugation and persecution of increasingly hopeless and aggravated Palestinians.” How anyone could have exploded with rage at the utterance of such a statement in 2006 indicates just how comparatively stifled the public debate was at that time. However much “pro-Israel” lobbyists may wish to limit public debate today, it’s impossible to imagine such a comment generating anything like the same opprobrium that was hurled at Carter then — ironically resulting in lots more copies of the book being sold. Carter never could have added enough Israel-sympathetic qualifiers to quell the backlash, such as his prescription that “the Arabs must acknowledge openly and specifically that Israel is a reality and has a right to exist in peace, behind secure and recognized borders, and with a firm Arab pledge to terminate any further acts of violence against the legally constituted nation of Israel.” Neither did Carter’s fond reminiscences about his early travels to Israel in 1973, when he was governor of Georgia and preparing to soon run for president, blunt any outrage. “Having studied Bible lessons since early childhood and taught them for twenty years, I was infatuated with the Holy Land,” writes Carter, and he thus eagerly accepted an invitation to voyage there. (Come to think of it, Carter was ahead of the curve in making Israel a go-to pilgrimage destination for any ‘serious’ presidential aspirant.)

The treaty Carter brokered between Israel and Egypt stands apart from the subsequent “Abraham Accords” under the first Trump Administration, which purportedly created “peace” between countries that had not been and would never realistically be at war with Israel: the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco. On the other hand, Egypt had fought multiple major wars with Israel in the years preceding the Camp David accords of 1978, and resolving that state of war can be reasonably viewed as a genuine diplomatic achievement, even if the “comprehensive” solution that Carter had sought was indefinitely shelved. No representative of the Palestinians was present at the Camp David negotiations. Coming into office, the Carter Administration had indicated that it wanted a “final settlement” to the Arab-Israeli conflict, which would necessarily have to include some redress of Palestinian territorial grievances and desire for self-government. But Carter followed along with the pre-existing policy to refuse direct dialogue with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), thereby affirming a position whose genesis he attributed to Henry Kissinger.

Not too dissimilarly from the approach later popularized by Donald Trump and Jared Kushner, the Carter diplomacy coincided with a $5 billion plan to sell 200 fighter jets to Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. This after Carter entered office piously vowing to inaugurate a new doctrine of “human rights,” and with it, a diminution of US international arms sales, which had skyrocketed over the preceding decades. As his term progressed, Carter gradually dialed down the evangelizing “human rights” talk that characterized his initial foray into US foreign policy doctrine.

Advocates of Palestinian self-determination were not particularly thrilled with the Carter legacy, despite how assiduously he touted the Egypt-Israel treaty as one of his crowning achievements. The Nation editorialized that Carter was more preoccupied with short-term electoral concerns than the comprehensive “peace” that he came into office pledging to pursue: “No settlement… can be arranged until international pressure is brought upon Israel to accept one, and no single individual can bring more pressure to bear than the President of the United States. Yet, as we all know, no President feels that he can carry New York State unless he kowtows to the Israeli leadership.”

Carter also came to power with an unflappable focus on mitigating nuclear brinksmanship, but as with Israel-Palestine, political factors intervened. One of his chief diplomatic surrogates during the 1976 presidential campaign, Averell Harriman, is recounted in the memoirs of Soviet ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin to have imparted candidate Carter’s conviction that “the central issue of the modern times” would necessarily be “the prevention of nuclear war.” Carter himself was a nuclear submarine engineer while serving in the Navy.

But as the 1980 election approached and it was determined that “strength” must be projected to fend off Ronald Reagan, Carter issued Presidential Decision Directive 59, which proclaimed Carter’s updated policy conviction that for the US to emerge victorious in nuclear war, “flexible sub-options” must be added to the potential target list, to include a “broader set of urban and industrial targets,” namely “political control targets.” Which is to say that Carter’s contribution to US nuclear doctrine was to ratify the permissibility of dropping nuclear bombs on Soviet cities.

A contemporaneous memo to Zbigniew Brzezinski, Carter’s bombastic National Security Advisor, mentions “that the Republican platform includes a lot of nuclear war-fighting doctrine,” and Carter’s new directive would be needed “to clarify our policy and leave no room for confusion” — a revision to nuclear war policy for manifestly electoral reasons. “The world moved one giant step closer to nuclear war because Jimmy Carter wanted to serve another four years as President,” wrote Alan Wolfe in The Nation in December 1980.

Notwithstanding how relatively hollow the “human rights” pieties proved to be during Carter’s presidency, they did prove significantly more conducive to his post-presidential activities. Carter could have easily spent all his time delivering lucrative speeches or sitting on corporate boards, but instead immersed himself in arduous diplomatic work, leveraging his unique standing as a former president. This included negotiations with the Supreme Leader of North Korea, much to the distaste of then-president Bill Clinton, and especially in relation to Israel-Palestine, with Carter becoming the only American statesman with the requisite standing to mediate between Israel and Hamas. Carter reported personally obtaining a ceasefire commitment from Hamas in 2008, ahead of the first Gaza war, which Israel proceeded to reject. Designations of Hamas as prohibited “terrorists,” or the subsequent denunciations from such pressure outfits as the ADL, had little impact on Carter — again one of the few virtuous uses of ex-presidential stature in the historical record.

The odes to Carter following his death contained some cursory mention of his Israel-Palestine endeavors, but it really may be one of the most singularly taboo-breaking contributions to public diplomacy undertaken by any former president. Some of it might be seen as atonement for his shortcomings while in office — but it was laudable all the same. Also impressive: that Gerald Ford had the foresight to laud it from the grave.

People younger than Boomers like me have never experienced an administration that had a relatively even-handed foreign policy regarding Israel/Palestine. The US has always favored Israel, but the slavish devotion to the Jewish ethnostate by bipartisan US polity has gotten completely out of hand. That and hatred of Russia and defense of the unipolar empire are the keystones to the uniparty world view.

Carter tried to tell us we were living beyond our means, using too much energy and going in the wrong direction as a nation. He was mercilessly ridiculed by the MSM, treated like a fool and now proved to be correct. I admired him for using diplomacy to free the hostages in Iran with no war to prove how tough the US was. But, once again, this was presented as a weakness, not a strength. Like many leaders he took bad advice that led to unforeseen consequences. He was a good human being who didn’t try to enrich himself while in office or out — more than can be said of the “leaders” who followed.