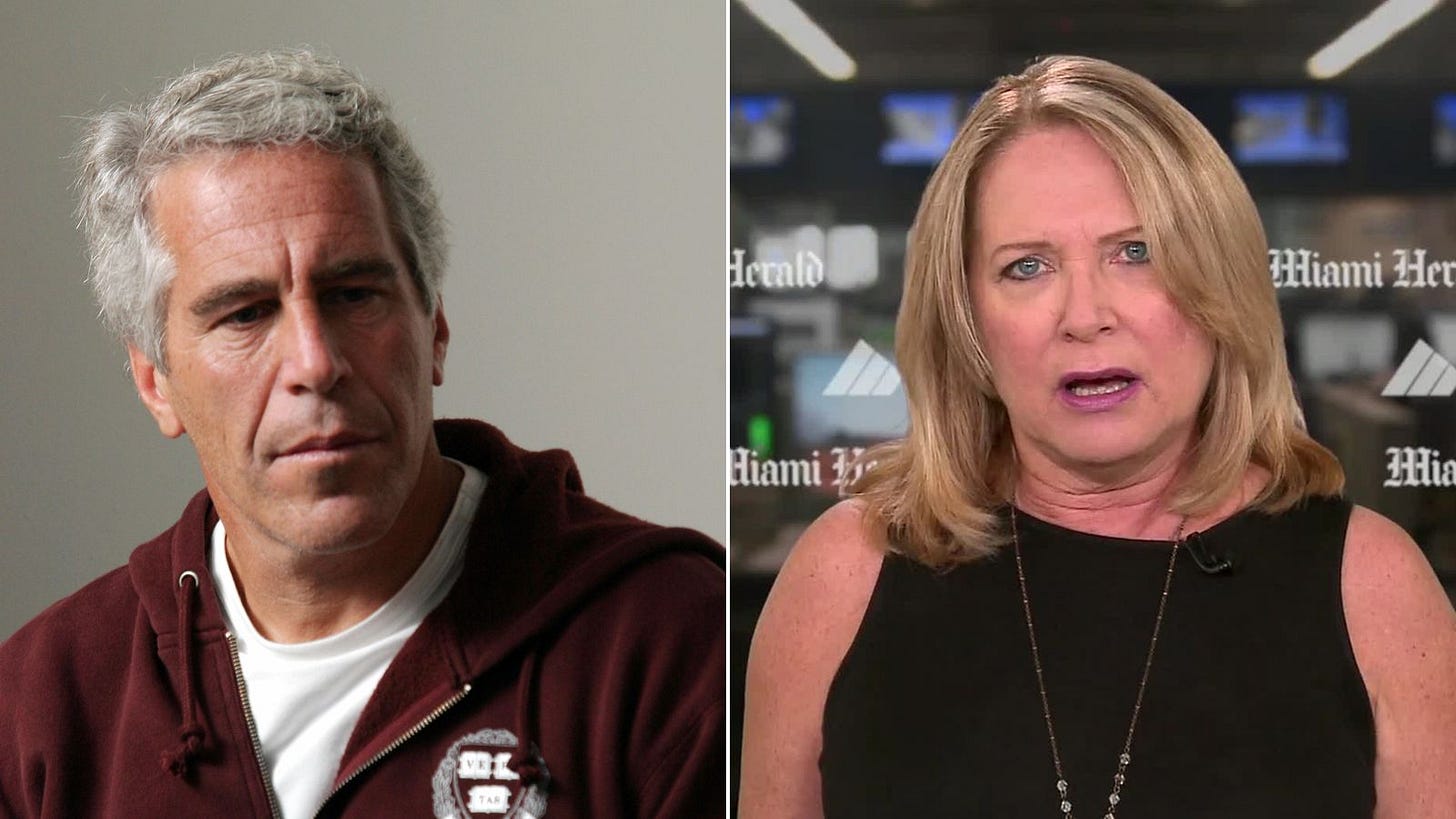

Julie K. Brown: Groundbreaking Epstein journalist, or ridiculous myth-peddler?

Julie K. Brown tells me she is “swamped” at the moment, and I have every reason to believe her.

Few journalists would be in higher demand during a spell of resurgent Epstein mania than Brown, whose 2018 series in the Miami Herald is credited for having generated a tsunami of public interest and political outrage around the issue. Not only that, it was those very articles, according to Brown, which catalyzed renewed prosecutorial action against Epstein. Brown reports in her 2021 book, Perversion of Justice: The Jeffrey Epstein Story (named after the seminal Miami Herald series) that “almost immediately” after her first installment went to print on November 28, 2018, prosecutors in the Southern District of New York alerted their boss, US Attorney Geoffrey Berman, who then quickly signed off on a revamped federal investigation — which ultimately culminated in Epstein’s July 2019 arrest, his death in custody the following month, and eventually Ghislaine Maxwell’s July 2020 arrest and December 2021 conviction. And here we are today. The Department of Justice itself has confirmed the influence of Brown in stimulating this sequence of events; references to her work are littered throughout the 2020 DOJ report on Epstein’s original prosecution in Florida, and the demands for reappraisal that erupted over a decade later. If nothing else, it’s impossible to deny that Brown has gotten results on a scale that most journalists could scantly imagine.

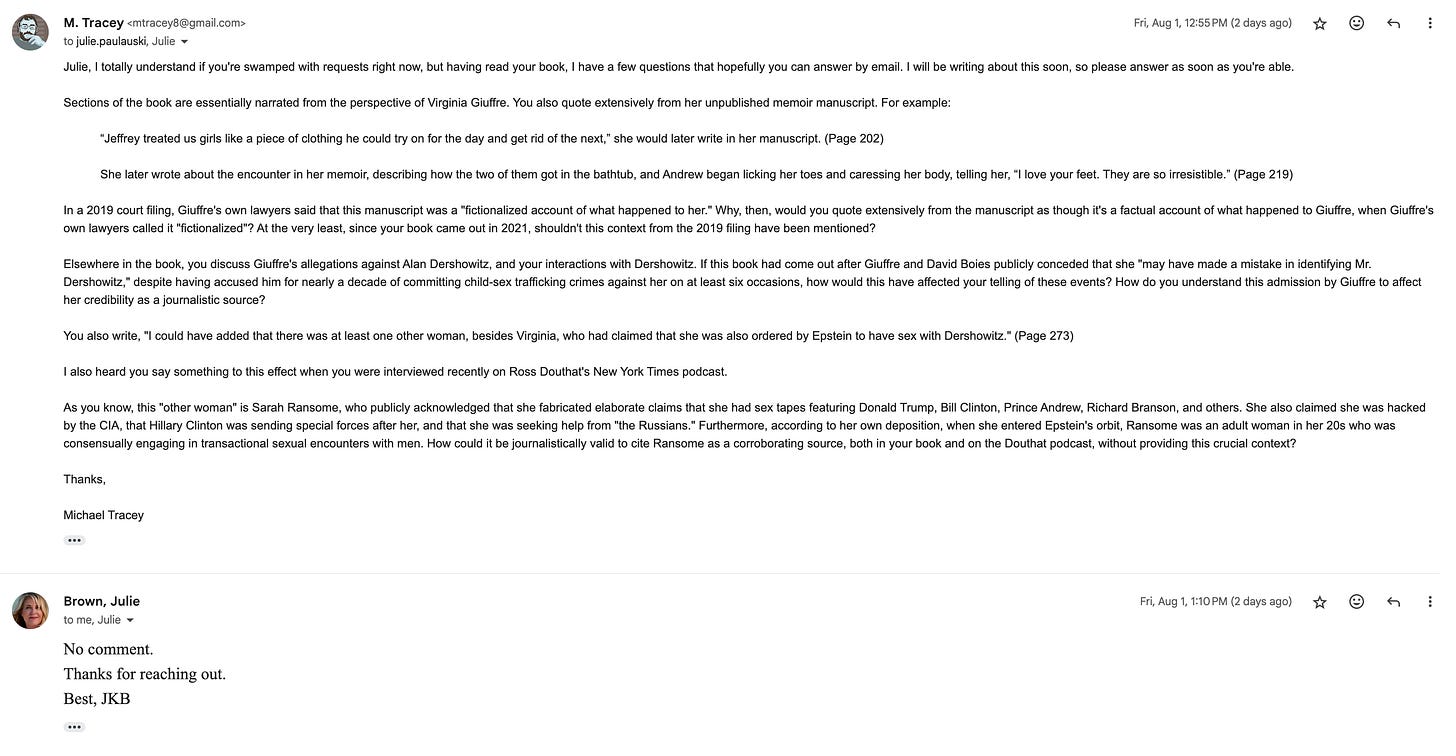

So in the midst of the latest Epstein uproar, and Brown again making the rounds as one of the nation’s leading journalistic experts on the topic — perhaps the leading expert — I read her book. I also re-read her original Miami Herald series; I watched or listened to several of her media appearances; I reviewed various litigation she’s been party to over the years. And then I had a few pertinent questions, which seemed (at least to me, but maybe I’ve gone nuts) completely reasonable. So I first invited her on a Substack livestream, and she indicated she was too busy. Fine, no problem. I then sent her a list of questions by email, in hopes she’d supply a response for this article. Her reply? “No comment. Thanks for reaching out.”

No comment? Really?

I have to say, it’s incredible how if you just gently pull at various threads in this tangled mess of a story, so much of it seems to unravel — and without any particular herculean effort. It’s just that hardly anyone seems to make any effort. At all. The more I dig in, the more information I gather, the more I’m convinced that approximately 90% of what people think they know about the Epstein “matter,” and then project outwards into a fever-pitched political/cultural/legal narrative, is either wildly exaggerated, wholly unsubstantiated, or straightforwardly fictitious. Much of that has to do with the media’s utter refusal to apply a modicum of critical scrutiny in their copious coverage, for a variety of potential reasons: it’s forbidden to question “victims,” we have to “believe survivors,” they sense a politically embarrassing issue to use against Trump, etc. etc. etc. Whatever the reason, it’s created a public apprehension that I maintain is approximately 90% unfounded. And a big reason for that, I’m sorry to say, is Julie K. Brown.

When I started Brown’s 2021 book Perversion of Justice, I assumed it was going to be a detailed and forensic journalistic account of her influential reporting on Epstein. Instead, much of it turns out to be personal memoir — chronicling the life and times of Julie K. Brown. At certain points, you can almost hear the editor coaching Brown to pad her wordcount in order to justify the book-length project. And thus appear passages such as: “When most people think of Florida, they think of beaches, Disney World, orange juice, or fishing. There are some truly magical, beautiful places across the Sunshine State.” Why does this sound like a loosely copy-and-pasted High School homework assignment on the subject of “Florida”? Whatever…

We also learn about Brown’s tribulations with her on-and-off boyfriend, whom she calls “Mr. Big” — which I didn’t realize was the moniker of Sarah Jessica Parker’s boyfriend in Sex and the City until a female recently informed me. Brown bemoans that once her Epstein reporting began to garner a lot of attention, Mr. Big grew “jealous that perhaps I was seeing someone else, which didn’t make sense because our relationship was never exclusive, especially on his part.” I am truly at a loss for what relevance the exclusivity or lack thereof in Brown’s relationship with her “Mr. Big” is supposed to be. Nonetheless, Brown writes, “In the midst of the biggest success of my career, he couldn’t even bring himself to be happy for me. For the first time during all our years together, I didn’t have the time or even the yearning to cry over him.” OK.

More importantly, when it comes to parts of the book that more directly relate to her Epstein reportage, massive red flags emerge that would be totally lost on the average reader.

Entire chapters are uncritically narrated from the perspective of Virginia Giuffre, the marquee Epstein accuser whose elaborate child sex-trafficking tales continue to form the basis of what people claim to believe when they posit the most scandalizing, dramatic versions of their Epstein theories. I contend that Giuffre has been indisputably proven to have been a serial fabulist. But even if you disagree with my characterization, and somehow believe she’s totally credible, what Brown does is still shocking.

Brown narrates large swaths of her book not just by citing Giuffre, or using her as a source, but quoting verbatim from sections of Giuffre’s unpublished memoir manuscript. A recap for the uninitiated: in 2011, Giuffre received $160,000 from the Daily Mail to participate in an interview and turn over the infamous photo of herself with Prince Andrew (the authenticity of which is still disputed). Subsequent emails between Giuffre and the Daily Mail journalist, Sharon Churcher, show the two strategizing about how to keep the payday going and secure Giuffre a lucrative book deal. One great strategy, they mutually agree, would be to toss into the prospective manuscript the names of whichever prominent individuals Giuffre can recollect who may have been in Epstein’s orbit. Literary agents are propositioned. Giuffre produces a draft manuscript, entitled The Billionaire’s Playboy Club, which is kept under seal for several years in litigation, but eventually released. In the manuscript, apparently written between 2011 and 2012, Giuffre claims to have had illicit sexual encounters with, among others, former Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell, the granddaughter of famed French explorer Jacques Cousteau, and a Harvard professor named Stephen.

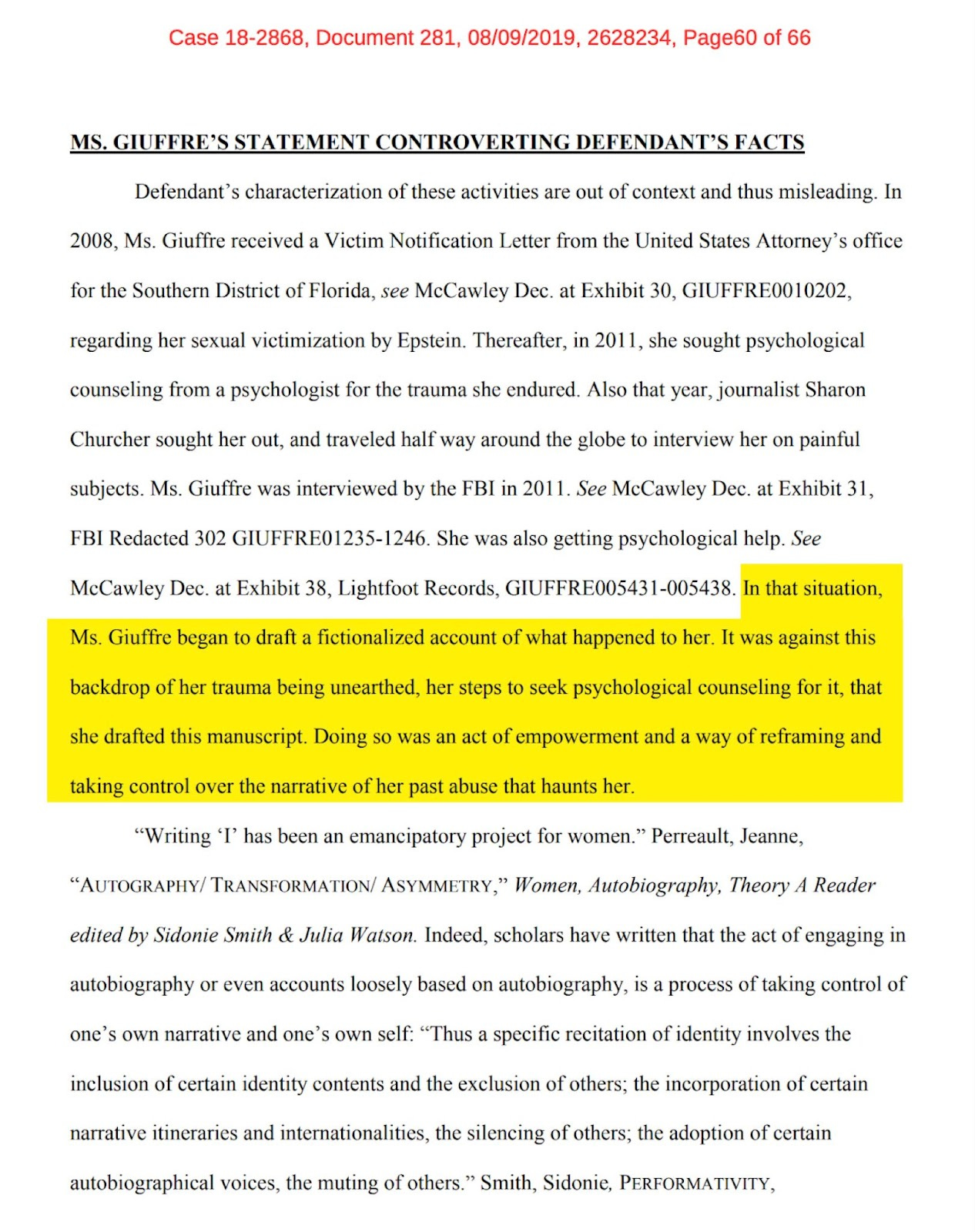

The issue of the unpublished manuscript kept coming up in various ongoing litigation, until finally, in 2019, Giuffre’s own lawyers admitted the manuscript was “fictionalized” — and purportedly written as part of a therapeutic process by which Giuffre had sought to “unearth” her “trauma” as an “act of empowerment,” and to set about “reframing… the narrative” around her alleged past sexual abuse. She had also obviously been hoping to profit off this writing exercise, but the lawyers shrewdly leave that part out. Nonetheless, they concede that their client, Giuffre, had written a “fictionalized” account of her experiences in the manuscript:

FYI: Giuffre said that thanks to the facilitation of her journalist friend Churcher, she did in fact obtain an agent, Jarred Weisfeld, who claims to have “agented many books in the Non-Fiction genre.” He’s also listed as the producer of TV offerings such as Charlie Sheen: Hollywood Black Book (2011) and The Unauthorized Saved by the Bell Story (2014). Weisfeld says he got his start as a VH1 production assistant, “where he pitched and sold a show to rap sensation Ol’ Dirty Bastard and subsequently became ODB’s manager.” This is the person with whom Giuffre was said to be collaborating on a purely therapeutic writing project to unearth her past trauma — separate and apart from any monetary incentive. If you believe that, I have a bridge in the US Virgin Islands to sell you.

Regardless, the admission from Giuffre’s own lawyers that her manuscript constituted a work of fiction was publicly divulged in 2019. Julie K. Brown’s book was published in 2021. And yet entire sections of Brown’s book are not just told uncritically from Giuffre’s perspective — they quote extensively from Giuffre’s manuscript, as though it’s a factual recitation of the relevant events, without Brown ever mentioning that Giuffre’s own lawyers said the manuscript was a work of fiction. Am I going nuts?

Here is Julie K. Brown, Perversion of Justice, page 218, describing Giuffre’s alleged sexual liaison with Prince Andrew:

She later wrote about the encounter in her memoir, describing how the two of them got in the bathtub, and Andrew began licking her toes and caressing her body, telling her, “I love your feet. They are so irresistible.”

They then had sex. “Afterward, he was not the same attentive guy I had known for the last few hours,” Virginia wrote. “He quickly got dressed, said his goodbyes and slipped out of my bedroom.”

Brown reproduces Giuffre’s manuscript account of being slapped by her mother:

“Of course, Mom didn’t meet me at the gate or the front door . . . No, instead she waited for me to come find her out back smoking cigarettes and having beer,” Virginia wrote. “She stood up from her seat and squinted her eyes with loathing and hatred, then she coldly slapped me hard in the face.”

Remarkably, Brown even appears to concoct brand new, clean-sounding quotes using Giuffre’s (fictionalized!) manuscript.

Virginia Giuffre, The Billionaire’s Playboy Club:

I introduced myself as “Jenna” which is what most people knew me as and told her l was on an employment trial to become Jeffrey’s massage therapist. She had a coy smile on her face that told me she knew exactly what I was on trial for. Something in my gut told me this wasn’t the first time a young girl had been trialed for the same position I was about to fill.

Julie K. Brown, Perversion of Justice, page 201:

“Hi, I’m Jenna,” Virginia said. “I’m here on an employment tryout to become Jeffrey’s personal massage therapist.”

Virginia suspected from the look on her face that it wasn’t the first time a girl had come for a tryout at Jeffrey’s house.

With a decent editor, Virginia Giuffre does seem like she potentially could’ve been a serviceable fiction writer, although some of her passages do come across as a bit “too perfect.” From The Billionaire’s Playboy Club:

The funny thing was they didn’t seem appalled at all by my statements, rather entertained if anything. Jeffrey called me a “naughty-girl” with that wry smile of his, and half playful and half defensive, I answered “no I’m not, I’m really a good girl, just always in the wrong places” he then replied, “It’s OK, I like naughty girls” and rolled over onto his front side to expose his complete nude self. He wasn’t the first man to show me his penis, so I wasn’t shocked at the appearance of his manhood but I was incredibly shocked at his complete ease to present himself with an erection. I tried to ignore it waiting to follow the next directions off of Ghislane [sic], who surprisingly now stood behind me bare breasted. Before I had a chance to even think of replying hastily she began to slowly undress me, while Jeffrey started to stroke his manhood while watching us. She unbuttoned my blouse and removed my bra, revealing my bosoms. Cupping them in her hands she moved her lips across my nipples, licking and teasing them with her tongue making them cold and stiff.

And then comes Julie K. Brown, repackaging and tweaking Giuffre’s paragraph for clarity and concision, without a hint of critical detachment about any of this. From Perversion of Justice, page 201:

They didn’t seem appalled at all, but instead teased her for being such “a naughty girl.”

“Not at all,” Virginia replied defensively. “I’m a good girl. I just was always in the wrong places.”

“It’s okay,” Jeffrey replied. “I like naughty girls.”

With that, he flipped over, exposing his erect penis.

She looked at Maxwell for guidance, but the proper English lady was now topless. She began to undress Virginia as Epstein stroked himself. Maxwell slid off Virginia’s skirt and underwear and began fondling her.

This goes on and on. Whether she’s directly quoting from it, paraphrasing it, or inventing new quotes based on it, Brown makes extensive use of this unpublished Giuffre manuscript as though it represents a credible factual account of the events chronicled therein — and never makes any mention that Giuffre’s own lawyers said the manuscript was “fictionalized.” The average reader of Brown’s book would have absolutely no idea about this crucial context. They would likely just assume that any material used by Brown was solid reportage, vetted and verified, because after all, Brown is one of the country’s foremost journalistic authorities on all things Epstein. Her acclaimed reporting in the Miami Herald is what generated huge renewed public interest in the story, even catalyzing prosecutors to investigate. So, certainly, this must be entirely credible stuff. It couldn’t possibly be a work of fiction that Brown is quoting, paraphrasing, reconstructing. Right?

And yet, there can be no dispute that Julie K. Brown extensively drew from an admittedly “fictionalized” manuscript to represent what the average reader would assume is a factual recitation of events. This is just crazy. How has no one ever bothered to point this out? Sometimes I feel like I’m the one who’s being “gaslit.”

Has it never occurred to Julie K. Brown that if Ghislaine Maxwell really did escort a 16 or 17-year-old Virginia Giuffre to Jeffrey Epstein for the first time, upon which the three engaged in a group sexual act, perhaps the government might have called Giuffre as a witness at Maxwell’s 2021 criminal trial — which occurred several months after Brown published her book? But the government never did so. Why might that be? They apparently had all this slam-dunk evidence of Maxwell’s criminal conduct, written down right there in Giuffre’s manuscript — and faithfully reproduced by Brown — which could have emphatically nailed Maxwell as a sex predator and trafficker. And although Giuffre (also known as Virginia Roberts) was mentioned throughout the Maxwell trial, she was never called to actually testify. As defense attorney Laura Menninger asked during closing arguments: “The government wants to try to claim that Virginia Roberts was also a victim. Where is Virginia Roberts? Why didn’t Virginia Roberts come and get on the stand and tell you that she was a victim? Use your common sense.”

What, then, are we to make of the reliability of Julie K. Brown’s overall narration of this affair?

It seems worth noting that Brown’s book is dedicated to Giuffre, so we know she must have a personal investment in attesting to her veracity, even after Giuffre’s April 2025 death — similar to Tara Palmeri and Nick Bryant. Brown also includes several federal prosecutors in her postscript acknowledgements, which likewise seems a bit curious. “To Geoffrey Berman, Maurene Comey, and Alex Rossmiller,” Brown writes, “thank you for having the courage to do what weaker prosecutors would not.” Is it common for journalists to profusely “thank” federal prosecutors in their book acknowledgements? I’d hope not.

Virginia Giuffre also played an outsized role in Brown’s original 2018 Miami Herald series, which according to Brown changed the course of her life and career. Surely, then, she’s going to have a tough time seriously engaging with any questions about Giuffre’s credibility (that is, if she’s ever actually asked such questions, other than by me.) Brown does briefly note in her book that “Giuffre admits that she was taking Xanax during much of the time she was with Epstein,” but doesn’t expand on this point. She could’ve added, for instance, that Giuffre told the FBI on March 17, 2011 that she was taking “up to eight” Xanax pills per day during the period she claimed to have been consorting with Maxwell and Epstein. Giuffre later acknowledged in a January 16, 2016 deposition that she told the FBI her excessive Xanax use had “affected [her] ability to recall certain events.” She also said in the deposition that she was routinely taking Ecstasy, drinking alcohol, and smoking marijuana.

I don’t mention any of this to “shame” someone for consuming Xanax, or any other drug. I mention it simply because if we’re going to take the word of this person as gospel — true beyond any reasonable doubt — and accept her claims as constituting a credible factual basis for the scandalous narrative that continues to engulf US politics, but we can’t even observe that by her own admission Giuffre’s memory had been impaired for a variety of reasons, including her over-consumption of a drug whose side-effects include impairment of long-term memory consolidation… then what are we doing here, exactly? Does anyone else not find this mandatory, enforced credulity to be utterly maddening?

It was in that same January 16, 2016 deposition — finally unsealed by the courts on January 9, 2024 (did anybody read it?) — that Giuffre describes her claimed sexual encounters with Alan Dershowitz in lurid detail, insisting on her absolute surety that they took place. (These are the same claims she would later retract.) “I am specific about the fact that I know I have been with Alan Dershowitz at least six times, if not more,” Giuffre testified under penalty of perjury. There was one instance, she said, where she and Dershowitz “had sexual intercourse on the chair while I was bent over.” Giuffre added, “He ejaculated. He was happy.” She claimed in another instance, she performed oral sex on Dershowitz in a limousine in Massachusetts. She also claimed with total certainty that various other encounters happened in various other locations. And then she eventually had to recant all her claims. (The precise wording of her November 2022 settlement with Dershowitz was Giuffre saying “I now recognize I may have made a mistake in identifying Mr. Dershowitz.” She “may have made a mistake in identifying” someone whom she vehemently insisted she had been sex-trafficked to on at least six separate occasions, having described each alleged encounter in graphic detail? OK, sure.)

Shouldn’t Julie K. Brown, ostensibly one of the country’s top journalistic experts on Epstein, be made to answer for the credibility of the person on whom she centrally relied for her Miami Herald reportage and book? Or am I crazy here?

On a recent episode of Ross Douthat’s New York Times podcast, Brown is interviewed. Among other things, she agrees with Douthat’s assertion that even though the Epstein story has “now been pulled into the vortex of Trump and MAGA and everything else... originally, this was a #MeToo story.” Brown happily acknowledges that while she was working on her Epstein series, “the #MeToo movement exploded. So it certainly helped my reporting.”

Then Douthat does something highly unusual for anyone in the media, which is that he ever-so-cautiously questions Brown about lingering credibility issues having to do with Giuffre. However, Brown evinces little willingness to concede much of anything. Instead she clings to her avowals of Giuffre’s untarnished veracity, including by claiming that “Virginia wasn’t the only one that accused Dershowitz of this.” Full excerpt here:

Douthat: What did happen to Virginia?

Brown: Well, Virginia went public, and she named names. And as a result of that, Alan Dershowitz was really the most vocal. And he attacked her just brutally at every juncture. Every time he was in front of a microphone, he said horrible things about her. It was very, very, very nasty.

Douthat: Well, in fairness — I mean in fairness to Alan Dershowitz — she had accused him of sex crimes.

Brown: Right. You didn’t let me finish.

Douthat: No, sorry.

Brown: Because I certainly agree that that’s enough to drive anybody crazy, especially if you’re wrongly accused. And he certainly felt that she had misidentified him. At the same time, Virginia wasn’t the only one that accused Dershowitz of this. There was one other victim that also accused him. So I agree that it — especially how the whole thing ended it, there’s certainly some question about whether her allegations — whether she was mistaken or not, let’s put it that way.

But I do think that the reason she ended up suffering so much trauma is every time something like this happens to a victim who’s been sexually abused — and she was as a child — you’re retraumatized. And so she had a lot of trauma in her life. And I’m sure that that led to her problems. Her mental health problems that ultimately led to her suicide.

So who is this “other victim” that Brown invoked as a corroborating source to bolster the credibility of Giuffre? Douthat obviously wouldn’t have had the background knowledge to recognize who Brown was talking about here. And after all, she’s the foremost journalistic authority on the entire Epstein matter, so Douthat may have collegially assumed that she’s owed some deference on basic factual issues.

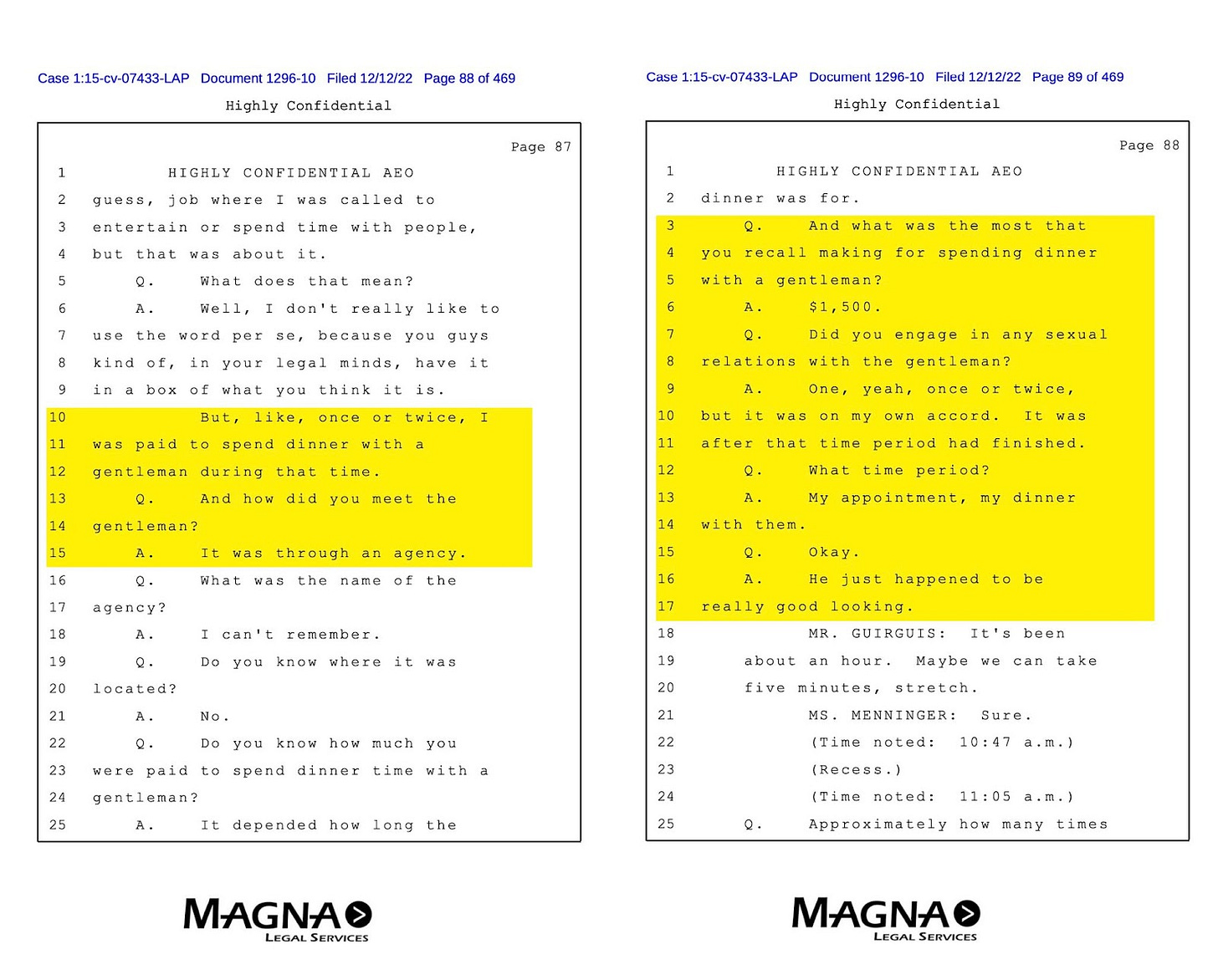

The “other victim” Brown references is Sarah Ransome. Who is Sarah Ransome? She’s a person who says she came to New York City from London, by way of South Africa, when she was 22 years old. So already, right off the bat, nothing Ransome says — even if we were to take it all at face value — would corroborate anything remotely related to any pedophilic sex-trafficking enterprise. Nonetheless, here are some noteworthy facts about Ransome. She said that when she first arrived in NYC, in 2006, she generated income by working with an “agency,” through which she would be “paid to spend dinner with a gentleman.” For such dinners, she said, she would receive $1,500. On certain occasions, she engaged in sexual relations with these “gentlemen” on her “own accord” — because, she said, sometimes they “happened to be really good looking.” So that’s what this adult, Sarah Ransome, was doing at the time she later claimed she was brutally enslaved in a heinous sex-trafficking ring.

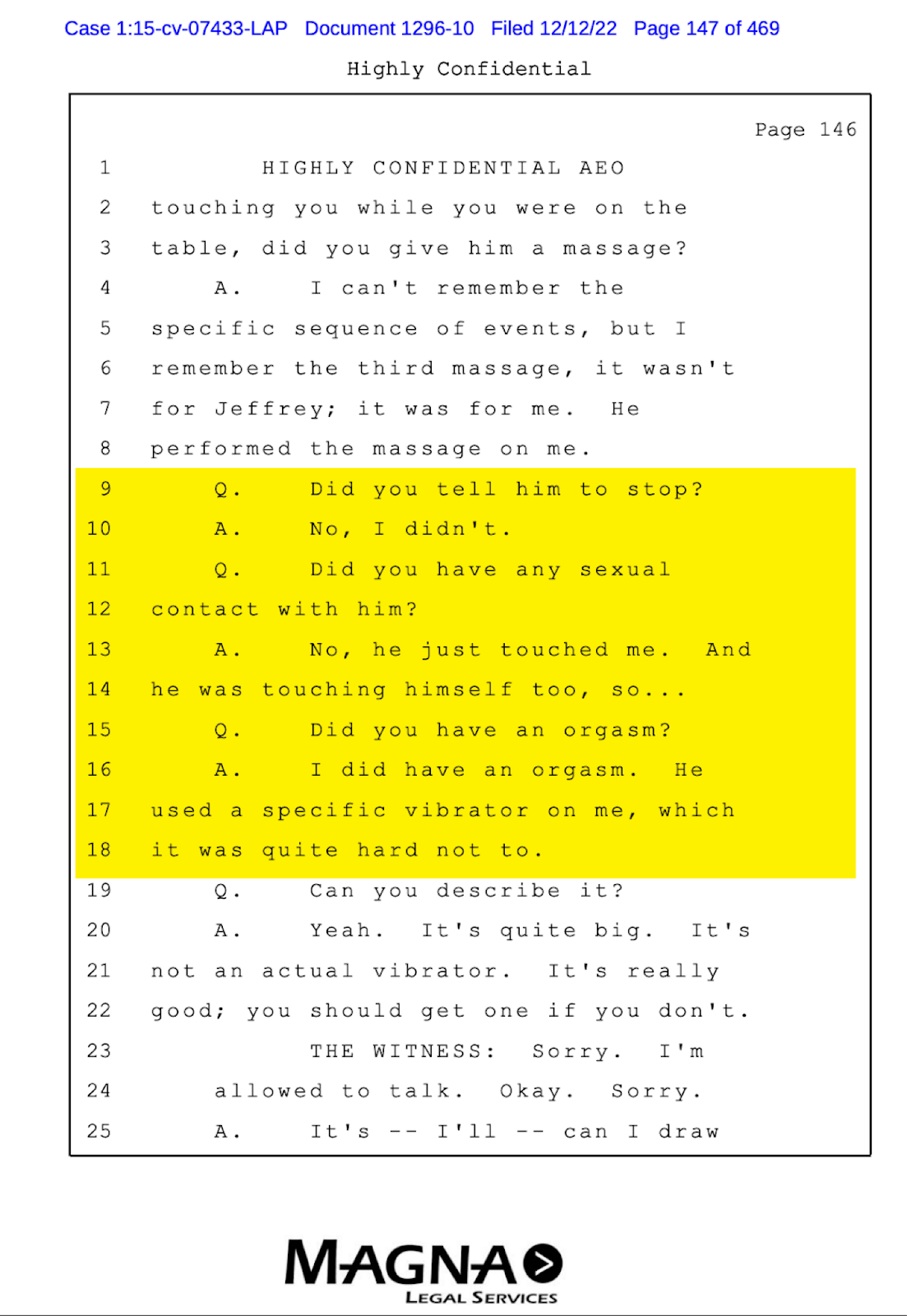

When she became acquainted with Epstein, Ransome said, he began to pay for all her living expenses, including accommodations (an elegant apartment on the Upper East Side), transportation, food, and medical visits. She started traveling with Epstein on his private jet to his private island, with the understanding that she was to be available to provide him with massages upon request. During one of these massage sessions, she said, Epstein asked her to undress and lie down on the massage table, which she did. Epstein then started to perform a massage on Ransome, she said, and it turned sexual. Ransome was asked if she told Epstein to stop. “No, I didn’t,” she said. She confirmed that she had an orgasm during the encounter.

This is who we’re told by Julie K. Brown is a sex-trafficking victim whose story somehow corroborates Virginia Giuffre, even though Ransome says she was at least 22 years old during all the relevant events — which would mean that even if one were to be maximally credulous of Ransome’s account, it would not substantiate any grandiose theories of a sprawling pedophilic sex-trafficking network.

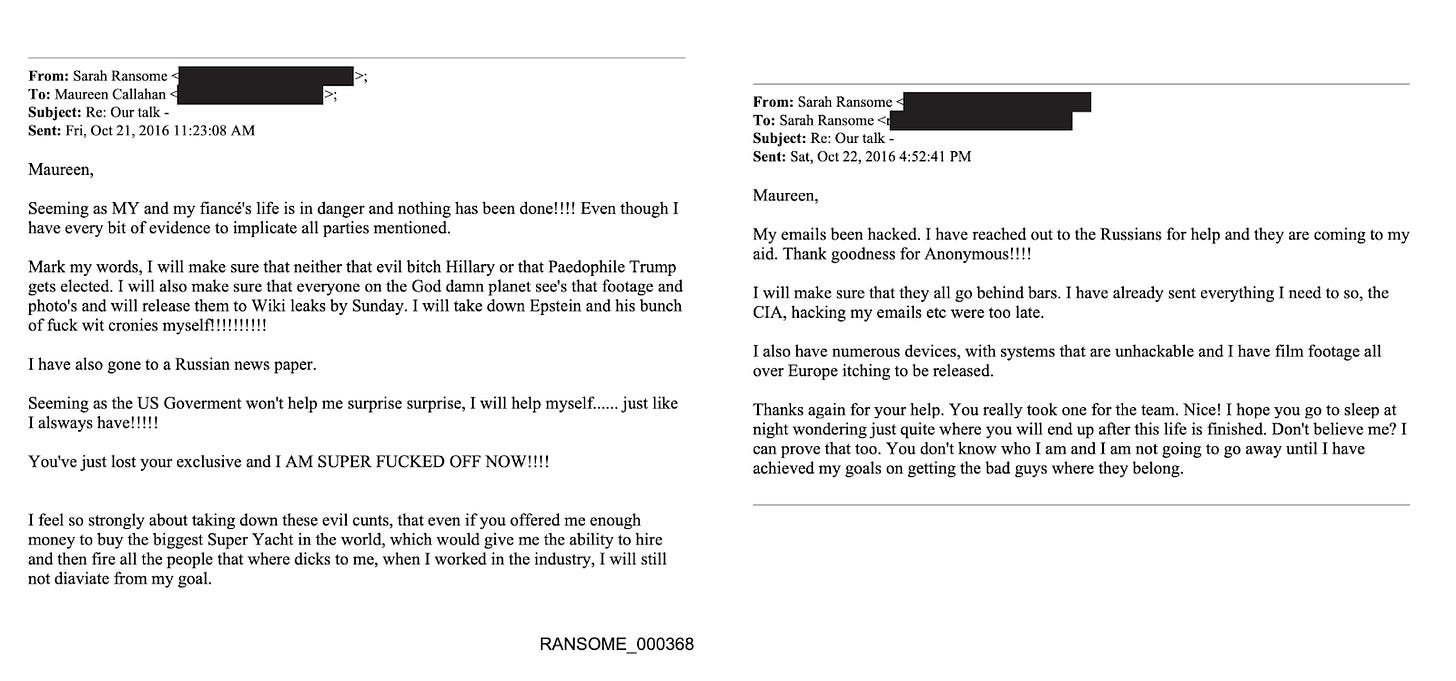

Ransome went on to descend into a hallucinatory spiral. She began an email correspondence with the New York Post in 2016, claiming she possessed sex tapes of Bill Clinton, Donald Trump, Prince Andrew, and Richard Branson, and had sent the tapes to secure facilities in Europe for safe keeping, because she was being hacked by the CIA and seeking help from “the Russians.” Her mission, she told NY Post journalist Maureen Callahan, was to single-handedly block either “that evil bitch Hillary” or “that Paedophile Trump” from getting elected in 2016. Feel free to peruse some of the email excerpts, and then ask yourself: Would I cite this person as a corroborating journalistic source for anything?

(For the adventurous, all the relevant emails can be read here.)

Ransome later confessed that she fabricated the existence of these supposed sex tapes for attention. Connie Bruck of the New Yorker reported in July 2019: “Ransome told me that she had invented the tapes to draw attention to Epstein’s behavior, and to make him believe that she had ‘evidence that would come out if he harmed me.’” Ransome also emailed Maureen Callahan and said, “I would like to retract everything I have said to you.”

Nonetheless, within a few months of this hallucinatory spiral, Ransome signed on with Virginia Giuffre’s high-powered legal team, led by David Boies, and submitted an affidavit dated May 1, 2017 in which she claims to have participated in a threesome with Dershowitz. The idea was that Ransome could corroborate Giuffre’s elaborate child sex-trafficking tales — but she ended up doing the opposite. In fairness to Julie K. Brown, she does say in her book that, with respect to any corroboration of Giuffre, “only one other victim, Sarah Ransome, has told a similar story about being trafficked. No other victims or witnesses have come forward publicly to corroborate Virginia’s sex trafficking allegations despite the fact that some of the encounters involved multiple girls and women.”

Fascinating. We’re told there could be over a thousand “victims” of this massive pedophilic sex-trafficking operation. Yet other than Giuffre and Ransome, not a single one of them has ever come forward alleging they were “trafficked” to any prominent third-party individuals, despite this forming the crux of what people so fervidly believe is being covered up at the highest levels. And the only two “victims” who did make such claims are proven fabulists. With Ransome having been an adult at the time of her claimed victimization.

Nonetheless, Ransome is heavily featured in the Netflix documentary on Epstein, Dirty Rich, whose viewership has surged in the past month. She’s identified onscreen with the title “Survivor,” as though that’s her profession.

In a February 17, 2017 deposition, Ransome is asked for her current occupation. “I’m a writer,” she says. Asked what she writes, she says, “Just stuff, you know? Just about factual stuff. You know, just a bit of this, bit of that.” She says she’s never been paid for her writing, and it’s “more of a hobby.” Nonetheless, she was able to maintain what appeared to be a rather comfortable seaside lifestyle in Catalonia, Spain.

The source of Ransome’s income later became clearer. She was one of the named plaintiffs who sued Epstein’s estate, leading to the creation of the Epstein Victims Compensation Program. Despite being an adult at the time of her claimed sexual victimization, she would’ve been eligible for millions in payouts, although the exact amount she received has not been disclosed. And she’s now suing yet again, along with another purported Epstein victim, Maria Farmer, for $600 million. (Farmer also says she was an adult in her 20s when she was purportedly victimized.) This time, US taxpayers would be on the hook for the payouts, as the target of the new class-action lawsuit is the US federal government.

Ransome also wrote a book entitled Silenced No More, published in 2021 by HarperCollins, which also published Julie K. Brown’s book the same year. Strangely, Ransome’s book contains no mention of Dershowitz. But she does recount how she made contact with Giuffre’s lawyers, asking them, “Is there any way I can help with Virginia’s case?” Ransome then takes credit for providing what she says was a “corroborating account” that really helped Giuffre.

Julie K. Brown is evidently in agreement with Ransome, whom she was still citing as of July 2025 as a corroborating source for Giuffre. Indeed, Brown had previously played an instrumental role in furnishing these two with felicitously “corroborative” press coverage:

Maybe I’m crazy, but could someone please explain to me how it could possibly be sustainable for Julie K. Brown not to be asked about any of this, as she again makes the media rounds to comment authoritatively on the latest iteration of the Epstein saga? She’s been on a million different podcasts, TV shows, and so forth in the past several weeks. She’s supposed to be among the country’s top Epstein Experts — if not the top expert. And when I very nicely asked her some of these questions, she simply replied: “No comment. Thanks for reaching out.”

I also find it strange that Brown says she was inspired to embark on her Epstein reportage in the first place by a sordid 2016 lawsuit in which an anonymous woman claimed to have been violently raped as a 13-year-old by both Donald Trump and Jeffrey Epstein. The day the anonymous accuser was supposed to hold a press conference, she supposedly disappeared and dropped the lawsuit. It later transpired that the whole bogus episode was orchestrated by Norm Lubow, a former producer on the Jerry Springer show who previously claimed to have been involved in a plot by Courtney Love to kill Kurt Cobain, and also claimed that he sold drugs to OJ Simpson on the night of the 1994 murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman. That’s what inspired Julie to cover Epstein? Really?

In another bizarre twist, Brown was sued in 2022 by multiple purported Epstein victims, one of whom, Courtney Wild, alleged that Brown falsely claimed in her Perversion of Justice book that Wild was raped by Epstein. In the book, for which Brown reportedly received a $1 million advance, Brown writes that Wild told her, “I can’t remember the exact time he raped me,” and that Wild “told the FBI the times that she had sex with him when she was underage.” But according to the lawsuit, Wild “never had sexual intercourse with Epstein and was never raped by Epstein” — and Brown knew these statements were false and defamatory when she wrote them in her book. Brown is also alleged by another purported Epstein victim, Haley Robson, to have threatened Robson that she would be “making the biggest mistake of [her] life” if she did not cooperate with Brown for the book. Brown went on to write in the book that Robson was “giddy with excitement” about receiving $200 for recruiting another teenage girl to massage Epstein. According to Brown, Robson advised this other girl, who was 14, to lie and say she was 18 if Epstein asked how old she was. Epstein did in fact ask how old she was, according to Brown, and “she lied, telling him she was an eighteen-year-old senior at Wellington High School.” Yet another purported victim of Epstein also filed suit, claiming she was misidentified by Brown in the book.

Am I the only one who finds all this completely insane? Please advise.

Michael, great reporting. I always learn a lot when I read you. When you offer political opinions, I usually don’t agree with them, but your reporting is always objective and in depth, so I love reading it. And I respect your reporting so much, that your opinions that differ from mine always provoke thought and cause me to challenge my assumptions. So, thanks for all of the hard and honest work you do.

Could the mainstream media be any worse? This woman profiting off of lies with no regard for the selfsame victims she claims (through labored tears im sure) to advocate for--despicable. (jfc those nauseating passages about her pathetic social life, are you a journalist or are you writing a telenovela?)

No matter how low my opinion of mainstream media has gotten over the years apparently it's never low enough. I'm glad at least you're out here, because as hard as it is for the 'brrrrr Pedophilic fetus eating monsters' crowd to stomach there is nuance to these stories and the actual truth matters.