Yes, Americans Overwhelmingly Opposed US Entry into World War II

The reaction to my September 23 article, “A Fairy Tale Version of World War II is Being Used to Sell the Next World War,” has been significant. Many people expressed praise and appreciation for the article, while many others expressed fury and denunciation. Much of the fury and denunciation seems to derive from the supposition that I’m only discussing this topic in the first place because my ultimate purpose is to undermine support for interventionist US policy in Ukraine. As such, a large portion of critics have started with the premise that I am personally “bad” — and then reasoned backward from there.

One of these critics published a Twitter thread which received wide circulation as a supposed refutation of the article. I’m going to respond substantively to those criticisms in a moment. First, I want to point out that this particular critic, Jonathan Katz, has spent years expressing fanatical personal hatred of me. To my knowledge, I’ve never met Katz. So this hatred cannot stem from any grudge related to how I’ve personally wronged him. Nevertheless, beginning in 2016, and continuing to the present, Katz has been extremely consistent in expressing his fanatical personal hatred. A recent example is when he alleged that I’d attempted to make the case for “Jews being responsible for the Holocaust.” No one operating with even the slightest smidgeon of rational thought can sincerely contend that this is the case I’ve been attempting to make. It’s an utterly incoherent reading of everything I’ve ever said. The only way the contention can be understood to be coherent is as an expression of psychotic personal animus. Which, accordingly, is exactly what Katz has been expressing for roughly six years straight.

Katz apparently deletes his tweet history, so I can’t access every psychotic personal attack he’s unleashed since 2016. He apparently just started posting his private messages to me though, in furtherance of his bizarre six-year personal vendetta. So here’s an illustrative excerpt from that exchange he initiated:

The last unsolicited message he apparently sent me was, “Stop pretending to be a journalist” on March 29, 2019. In the past month, he’s alleged that I’m either “a Nazi who believes Nazi things too” or “an absolute bleeding idiot” — and that I have “the brain of a child.” In July, he called me “a coward and a poseur.” Every tweet prior to July has apparently been deleted. However, this should be sufficient to establish that Katz has repeatedly expressed bizarre personal hatred toward me for an extended period of time. Whereas I’ve never had any real reason to take interest in Katz. I certainly don’t know enough about him to hate him on a personal level, or to really have any feelings about him one way or another. I honestly have very little idea of who Katz even is or what he does. Again: for the past six years, my exposure to him has been almost exclusively by way of his constant expressions of fanatical personal hatred toward me.

All this being the case: I nevertheless had an hour-long conversation with Katz this past Sunday afternoon (September 25) when he opted to join my open-invitation audio session on Callin. The purpose of the session was for anyone with a criticism of my article on World War II to challenge me with counter-arguments. You can listen to the Callin session, which stretched to over four hours, at this link. Here’s my underlying point: even with people who have a years-long track record of spewing venomous personal hatred at me, I’m still willing to engage in as substantive an exchange as possible, about the actual merits of what I’ve said or written. Because I’m interested in defending my arguments on the substance.

So with that in mind, I’m going to respond to Katz’s criticisms from the Twitter thread he posted September 24. Katz began the thread by declaring my article a “deeply dishonest piece of lying garbage that frequently veers into Nazi-sympathizing agitprop.” In our Callin exchange, Katz seemed to deny that I should interpret this characterization of my article as another of his venomous personal attacks. The characterization of the article proffered by Katz is not exactly what one would normally interpret as an invitation to substantive dialogue, but nonetheless, I’m going to address Katz’s criticisms on the substance.

The first criticism Katz makes is that I “lied” in writing the following paragraph:

Public opinion polling then was in its infancy, but a poll taken by Gallup in May 1940 asked respondents: “Do you think the United States should declare war on Germany and send our army and navy abroad to fight?” 93% said “no.” Gallup apparently did not conduct any further polls specifically asking the direct “should we or should we not go to war” question until after Pearl Harbor. But campaigning for re-election on October 30, 1940, Roosevelt gave an indication about the state of public opinion when he pledged to an audience in Boston: “While I am talking to you mothers and fathers, I give you one more assurance. I have said this before, but I shall say it again and again and again: Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.” And on November 2, in Buffalo, Roosevelt declared: “Your president says this country is not going to war.”

Katz charges I “dishonestly imply that Gallup did not ask Americans if they supported risking war between May 1940 and December 1941. I guess you assumed no one would click the link?”

Of course, as anyone who can read plain English and is not demented by compulsive hatred will hopefully recognize, what I actually wrote was: “Gallup apparently did not conduct any further polls specifically asking the direct ‘should we or should we not go to war’ question until after Pearl Harbor.” As in, Gallup apparently did not ask a direct referendum-style question about whether respondents favored entering the war after May 1940, until December 1941. I was specifically and explicitly referring to that direct formulation of the question. Because in the link that I expressly included — apparently to cover up my lies, which would be an odd coverup strategy — no instances of the question formulated in that direct manner are listed after May 1940 and before December 1941. Yes, other questions in other formulations are cited, but I was specifically referring to that direct formulation of the question. In the archive found on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website — which is the archive I referred to and linked to — no polls asking the war-entry question in a manner as specific and direct as, “Do you think the United States should declare war on Germany and send our army and navy abroad to fight” are listed after May 1940, until December 1941.

If anything, my error was only citing the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website for a list of polls that were taken during 1940-1941. As it turns out, other polls did ask this direct question on many more occasions than had been listed in the museum’s website archive. I regret the oversight, because a more comprehensive review of the polls would have revealed the durability of public sentiment opposing US entry to the war:

January 1941: “If you were asked to vote on the question of the US entering the war against Germany and Italy, how would you vote—to go into the war, or to stay out of the war?”

Go in: 12%

Stay out: 88%

March 1941: “If you were asked to vote on the question of the United States entering the war against Germany and Italy, how would you vote—to go into the war, or to stay out of the war?”

Go in: 17%

Stay out: 83%

May 1941: “If you were asked to vote on the question of the United States entering the war against Germany and Italy, how would you vote—to go into the war, or to stay out of the war?”

Go in: 21%

Stay out: 79%

July 1941: “If you were asked to vote on the question of the United States entering the war against Germany and Italy, how would you vote—to go into the war, or to stay out of the war?”

Go in: 21%

Stay out: 79%

September 1941: “Should the United States go into the war now and send an army to Europe?”

Yes: 8%

No: 88%

September 1941: “Should the United States enter the war now?”

Yes: 21%

No: 79%

October 1941: “Should the United States enter the war now?”

Yes: 24%

No: 69%

October 1941: “Should the United States declare war on Germany now?”

Yes: 17%

No: 74%

October 1941: “Should the United States go to war now against Japan?”

Yes: 13%

No: 74%

November 1941: “It has been suggested that Congress pass a resolution declaring that a state of war exists between the United States and Germany. Would you favor or oppose such a resolution at this time?”

Favor: 26%

Oppose: 63%

Source for all polling data listed above: Public Opinion 1935-1946 (1951) by Hadley Cantril, Princeton University Press, and The Gallup Poll: Public Opinion 1935-1971 (1972) by George H. Gallup.

Katz inveighs that I neglected to mention a critical development which should have been “bleedingly obvious to anyone with even a passing familiarity with the course of World War II” — that is, the German invasion of France. According to Katz, my “lie” stems from my ignoring this development, which he suggests would’ve had an outsized effect on engendering US pro-war sentiment after May 1940. Katz correctly reports that Germany invaded France on May 10, 1940. However, as the above polling data demonstrates, US public opinion remained relatively constant even well over a year later — at least judging by polling questions that directly asked respondents whether they favored entering the war.

Franklin Roosevelt’s speech about the USS Greer incident took place on September 11, 1941, wherein Roosevelt (falsely) declared that Germany had initiated an attack on a US warship. This incident, plus the two subsequent instances of naval warfare initiated by the US on Germany in September-October 1941, appear to have possibly had some effect on public opinion. Recall: on October 27, Roosevelt declared, “America has been attacked… Hitler’s torpedo was directed at every American.” It would be odd if such jarring declarations from the longest-serving US president, who had just been re-elected to an unprecedented third term in November 1940, would have no impact on public opinion. Still, pre-Pearl Harbor, nothing close to a majority ever emerged in favor of US entry to the war — again, as judged by these most-direct formulations of the relevant polling question.

It’s true that other polling questions designed to gauge attitudes about various aspects of interventionist US policy — sending arms to Great Britain, etc. — show differing results. But what I was explicitly attempting to do here was focus on the questions which are phrased as directly as possible, in a referendum-style fashion, about whether the US ought to enter the war, or ought not to do so. And the results of these polls show consistent, overwhelming opposition to US entry all throughout 1941, up to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

So no, I did not “lie” about US public opinion during this period. If anything my error was not being more scrupulous about highlighting the durability of opposition to US entry into the war.

Katz also condemns what he suggests is my egregious misrepresentation of Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas’ views on US entry to the war. In his verbal Callin exchange with me, Katz denied that the opposition Thomas expressed to the “Lend-Lease” bill in 1941 could be reasonably characterized as “strident.” I would encourage everyone to read Thomas’ full testimony before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs on January 22, 1941. In the first paragraph of his statement, Thomas proclaims: “It is a bill to authorize undeclared war in the name of peace and dictatorship in the name of defendant democracy.” He adds, “That such a bill should be introduced at all at the request of the popular leader, President Roosevelt, on the eve of his inauguration, after an election campaign in which he gave not the slightest hint of asking such powers, is a technique completely at variance with democratic procedure.”

Thomas goes on,

If it is morale that [Roosevelt] wants and now thinks lacking, this bill is about the worst way to get it, because inevitably it awakens fear, suspicion, and mistrust in the hearts of millions of Americans. I do not speak without evidence from a large mass of my own unsolicited correspondence when I say that already this bill has been a great blow to American morale. If, and when we get into total war as a result of it, we shall find not only that that war will be resented by millions who now consider it unnecessary, but by millions who, encouraged by the supporters of this bill, now live in the fool’s paradise of belief that we can fight a partial and limited war with things and not with men.

Thomas concludes his opening statement with the following exhortation to members of Congress: “If you thus recommend this bill and thus hasten your country into total war, you may perhaps temporarily sweep a small majority of the people with you. But later, to my sons and yours, and to history, you will answer for blood and tears spilled in vain, for liberties lost that would have been saved, for the black-out of democracy over this great land where it might have shone with ever-increased splendor.”

I’m not sure how much more “strident” one could be in declaring opposition to a piece of legislation. Again, read the full testimony if you’d like. Let me know if you find any other statements from Thomas that might be reasonably interpreted as reflective of “strident” opposition to the “Lend-Lease” bill.

As further evidence that I’ve “lied” and egregiously misrepresented the views of Thomas, Katz posts an excerpt from Thomas’ 1951 memoir, A Socialist’s Faith. Here is the excerpt Katz posted:

Practically there were no alternatives but abject surrender on a global scale to fascism — in which would have been no lasting peace — or military action to end brutal aggression’s march to triumph. No longer was powerful America an island of a possibly contagious sanity in a war-mad world. I, the hater of war, chose as between circles of hell. I chose critical but active support of the war to a point where a decent peace might be possible. For that end I worked inside and outside the Socialist Party.

Katz claims my “lie” stems from not adequately acknowledging that in “in short order, Thomas would simply flat-out support the US going to war against the Nazis.” It might’ve been handy to also include the paragraph immediately preceding this one from the Thomas memoir, in which Thomas writes:

The war which many Americans now boast that we entered when we adopted Lend Lease became an all-out struggle when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. It is not to deny the guilt of the Japanese war lords to say that Roosevelt’s policy was headed toward war with Japan, and that Pearl Harbor was politically a godsend to him, although he might have preferred a less disastrous attack somewhere else.

Contrary to what seems to be Katz’s representation, Thomas never repudiated his strident opposition to “Lend-Lease” in 1941 — or even to his opposition to US entry into the war pre-Pearl Harbor. In fact, Thomas reiterated what he regarded to have been the rightness of his opposition. In the 1951 memoir, Thomas writes:

There is a feeling, curiously widespread when one reflects on the extent of American opposition to intervention in the war and our profound disappointment with the results, that no other course than that by which Roosevelt led us into war was possible or intellectually and morally defensible. For myself I see little in the present state of the world to warrant that conclusion. I still think that America might have kept out of war on terms consistent with constructive usefulness to mankind and that, as a result, her own security and the well-being of other peoples might today be less in jeopardy than they are.

Again, Katz alleges that my “lie” about Thomas in part owes to my ignorance that Thomas “in short order… would simply flat-out support the US going to war against the Nazis.” Of course it’s true that after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Thomas — along with other so-called “isolationists” of the time like Montana Senator Burton Wheeler and Charles Lindbergh — came to reluctantly support the US war effort. But until the very day before the Pearl Harbor attack, Thomas continued to express his strident opposition to US entry. From the book Norman Thomas: The Great Dissenter (2008) by Raymond Gregory:

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Norman and Violet drove to Princeton to retrieve some of the belongings Evan had left behind. It was at Princeton that they heard the news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. For Thomas, this was an irreparable defeat of his hopes that his children would not know a world war. As late as the day before, Thomas had written a letter to the New York Times again opposing any involvement of the United States in the war. Now he had to face the fact that he had met defeat “of the single ambition of his life: that [he] might have been of some service in keeping [his] country out of a second world war.”

After hearing of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Thomas was resigned that his efforts to keep the US out of the war had failed. He withdrew the letter to the New York Times. Thomas absolutely never renounced his non-interventionist advocacy — in fact, he continued to emphasize its correctness years later. In the 1951 memoir Katz cited as evidence of my “lies,” Thomas wrote:

In the campaign of 1940 I argued — I think correctly — that unconsciously, at least, drift to war was furthered by the fact that an arms economy was a more successful answer to unemployment than the New Deal had been. I admitted that there was a case to be made for entering the war with the banners of humanity flying, even though I thought the weight of argument was against it. But ethically, I contended, there was no case at all for sidling into war, or for Roosevelt’s assertions that steps logically leading to war led to peace, or for assuring the fathers and mothers of America that he would not send their sons into a foreign war. If it be true, as many of Roosevelt’s champions now contend, that under a democracy the people must be fooled into a war, even a necessary war, it is a dreadful condemnation of democracy.

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., the historian and later special assistant to John F. Kennedy, echoed Thomas’ point here in a May 9, 1948 article for the New York Times. Schlesinger, remarking on what he called “the Roosevelt problem,” presents the following quote from the book The Man in the Street (1948) by Thomas Bailey:

Roosevelt repeatedly deceived the American people during the period before Pearl Harbor... He was faced with a terrible dilemma. If he let the people slumber in a fog of isolation, they might well fall prey to Hitler. If they came out unequivocally for intervention, he would be defeated in 1940.

Schlesinger writes: “If [Roosevelt] was going to induce the people to move at all, Professor Bailey concludes, he had no choice but to trick them into acting for what he conceived to be their best interests.” Thus by 1948, the trickery and deception employed by Roosevelt during this period had been freely acknowledged both by Roosevelt’s erstwhile political opponents (Thomas) as well as his supporters (Bailey and Schlesinger.)

In the 1951 memoir, Thomas argues that his protestations throughout 1941 about “Lend-Lease” — namely that it would lead to direct warfare against Germany — were vindicated:

Evidence now available shows that so far was Hitler from disregarding danger from a “weak” America that he avoided the aggressive action against us that our open aid to his enemies invited in the hope of preventing or postponing as long as possible our full belligerent participation in war.

Also in the memoir, Thomas offers a defense of the “America First” anti-war group, which had since been heavily villainized, and continues to be villainized this very day. Thomas writes:

In many quarters it is still held against me that on two or three occasions, one of them at Madison Square Garden with Colonel Lindbergh, I spoke on an America First platform — and this by the same liberals who long since have quite rightly taken to their bosom Chester Bowles, later the able governor of Connecticut, who was a member of the executive committee of America First until its dissolution.

I always explained that I spoke for the Keep America Out of War Congress. Nevertheless, since I was sincerely anti-interventionist and sincerely convinced that the leadership of America First could not fairly be called fascist but was on the whole surprisingly successful in keeping down fascists and crackpots, I thought that refusal to cooperate by appearance on the same platform as Colonel Lindbergh would be a futile piece of self-righteousness, a failure to use an important opportunity.

Thomas even offers a personal defense of Lindbergh:

Charles Lindbergh was not an infallible military prophet or a great political thinker. He was an honest, courageous, patriotic American, hero of an epic deed, who spoke under a sense of duty, and steadily refused to exploit his enormous prestige for personal advantage. In short, he was the very opposite of the demagogue whom his enemies painted. He was very independent and he shunned advice on his speeches. Thus he blundered into his ill-fated Des Moines speech, generally regarded as anti-Semitic. I knew him well enough to believe that false. His speech was open in tense times to misinterpretation and he did exaggerate the role of Jewish-Americans in pushing the nation toward war.

I issued a statement deploring that fact but I never thought Colonel Lindbergh guilty of intentional anti-Semitism. He bore with dignity the President’s rejection of his offer of service after Pearl Harbor and quietly did what he could — and that was much — as an expert in aviation. I owe to him and to other honest leaders of America First, some of whom rendered distinguished service in World War II, this testimony in face of abuse going far beyond reasonable criticism. It is not healthy for the future that an honest effort to keep our country out of war should have been so unjustly stigmatized.

The Thomas memoir is well worth reading for many reasons, not least because it shows how adamant Thomas was not to repudiate his non-interventionist position in 1941 — but rather to affirm its correctness, even years after the war ended:

When Hitler attacked Stalin I did not prophesy easy victory for his arms but I did think and say that the choice between dictators in Europe was not worth the blood of our sons, and that there was more chance for American security and general decency in the rivalry of two dictators than in the absolute victory of one of them.

Another of the “lies” I’m alleged by Katz to have perpetrated is my declining to mention that Burton Wheeler — who collaborated with Thomas in campaigning for non-interventionism before Pearl Harbor — was a “Nazi sympathizer.” Some of the evidence Katz cites is a photo of Wheeler alongside Thomas and Lindbergh at a May 23, 1941 event in New York City — the Madison Square Garden event referenced by Thomas in the above excerpts. Wheeler was alleged to have made a hand gesture that could resemble the Nazi salute:

Interestingly, Thomas is in this same photo (partially cropped out at the far right) making a very similar salute. They were all saluting the American flag when the photo was taken:

Here is another photo from the event where Thomas is more visible (again, at the far right):

It seems radically implausible that Norman Thomas, on this one occasion, decided to discard his lifelong beliefs and make a hand gesture intended to broadcast his support for Nazism. Some may nonetheless take the view that for this one instant on May 23, 1941 — before endless cameras, and before a massive live audience — Thomas suddenly transformed into a Nazi. Katz links to an article in the New York Review of Books in which it is complained that Getty Images revised the caption of the image to excise the claim that Burton Wheeler, pictured at the left in the white suit, was performing a Nazi salute. The official Getty Images caption currently reads:

Left to right: Senator Burton K. Wheeler (1882-1975), Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974) and novelist Kathleen Norris (1880-1966) pledge allegiance to the American flag at an America First Committee (AFC) rally at Madison Square Garden in New York City, 23rd May 1941. They are giving the Bellamy Salute, which was replaced by the hand-over-heart salute the following year because of concerns about its similarity to the Nazi, or fascist salute used in Italy and Germany. The AFC was a pressure group opposed to US involvement in World War II. (Photo by Irving Haberman/IH Images/Getty Images) (AMF-57)

Katz alleges that I lied by not mentioning that “Wheeler was a Nazi sympathizer.” Even if Wheeler was a diehard, rotten-to-the-core supporter of Hitler, it would not have been a “lie” for me to detail the chronology of Wheeler revealing the existence of a secret military operation ordered by Roosevelt in 1941. Nonetheless, Katz’s source for the claim that “Wheeler was a Nazi sympathizer” is interesting. Katz cites an excerpt from a book called The Secret War Against the Jews: How Western Espionage Betrayed the Jewish People (1994) by John Loftus and Mark Aarons. Loftus is a former Justice Department official who has recently written a regular column for the “Ultra Orthodox” online magazine Ami. Here are the most up-to-date writings from Loftus:

Here is the excerpt from the Loftus book Katz posted:

The book’s footnote for the claim that Wheeler was “so pro-Hitler that he sent Nazi propaganda through the mail, using his congressional franking privilege” cites the following source: “The classified files of US congressmen who dealt with the Nazis are in the top-secret vault, 6th floor, Main Justice Department, private files of the attorney general. One of the authors reviewed these records in 1980 during the course of his government employment.” So in other words, there is literally no way to evaluate the primary source corroboration for this claim, at least as it’s presented in the book cited by Katz.

There was a controversy in 1941 whereby Wheeler was denounced for using his congressional franking privileges to send certain materials through the mail. In July 1941, General George Marshall received complaints that Wheeler had sent out postcards urging recipients: “Write today to President Roosevelt, at the White House, in Washington, that you are against our entry into the European war.” Here is the postcard, with a recipient’s objections scribbled onto it:

Is this the supposed “Nazi propaganda” that reveals Wheeler was “so pro-Hitler”? Hard to say. However, Wheeler did contemporaneously deny what he called “slanderous attacks” from Roosevelt and others alleging him to be a Nazi sympathizer. In his 1962 memoir, Wheeler insistently maintained that he had always “publicly condemned the Nazis’ racial and religious persecutions.”

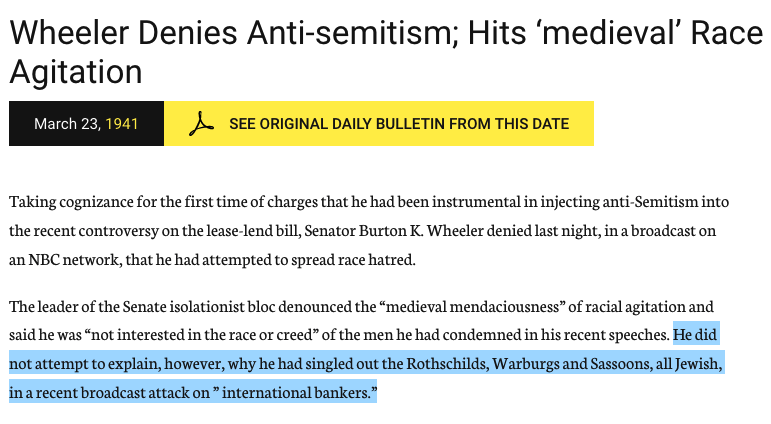

Katz cites another piece of evidence to prove I “lied” by omitting any mention that Wheeler was allegedly a despicable Nazi sympathizer:

Notably, Katz omitted the statement by Wheeler included in that Jewish Telegraphic Agency item:

Those of us anxious to preserve civil liberties and peace have been subjected to a smear campaign, but fact is not answered with fact, or reason with reason. Cries of ‘pro-Nazi,’ ‘Hitler agent’ and ‘anti-Semite’ are shouted at the opposition. This is bigotry in its vilest form. This is a return to the monarchical concept that the king can do no wrong.

Nothing I have said can be interpreted to give comfort to those people here or in any country in the world, who make a fetish of the persecution of any minority group. I denounce those who seek to play upon the passions and emotions of our people with this kind of medieval mendaciousness.

Today we witness legislative and administrative actions which inevitably must lead to the denial of the rights of minorities. A Lend-Lease bill, an alien concentration camp bill, an anti-strike bill, a wiretapping bill — these are the vehicles of one-man government. They will lead to chains and tears for the minorities in our land. Wave after wave of every kind of intolerance will roll over our nation. No minority group, economic, political, racial or religious, can be certain that it will escape the tide. These are the results of war and war psychology.

Since he ran for Vice President in 1924 alongside presidential nominee Robert M. La Follette, the most prominent Progressive Party figure in the country — on a ticket in alliance with the Socialist Party and the Farmer-Labor Party — it’s true that Wheeler had been an acid critic of Wall Street financiers.

For example, on May 28, 1941, Wheeler delivered a speech at an anti-war rally denouncing the “Rockefellers, Morgans, Dorothy Thompsons, Stimpsons, Knox[es], Walter Winchells” of the world whom he regarded as working to “plunge this nation into war.” Of course, the then-deceased business magnates John D. Rockefeller and J. P. Morgan were not Jewish, despite Wheeler having “singled them out” on this occasion, along with the heirs to their fortunes. Even so, on the counsel of Norman Thomas, Wheeler throughout 1941 sought to consciously avoid giving “even the suspicion of racial intolerance” in his speeches, according to a 2019 biography of Wheeler. He also actively recruited Jewish Americans to join the non-interventionist cause. Wheeler wrote to a prominent Jewish business executive:

All my life I have hated intolerance and bigotry... I am of the firm conviction that we are not going to stamp this out by embroiling ourselves in the quarrels of Europe, even if the objective of the present war is to crush a European madman. I say this because I believe that Hitlerism was born in the degradation and poverty that was visited on the German people after the last World War.

But again, even if it were proven 100% true that Wheeler was a deep-seated, hardcore Jew hater and Nazi lover, it would not somehow make a “lie” my discussion of Wheeler in the article. The purpose of this discussion was not to litigate Wheeler’s personal motives, but to point out that he was the first to reveal a secret US military operation ordered by Roosevelt, and for this was denounced as treasonous. Here is what I wrote in the article:

In contravention of what the Navy Secretary, Knox, had assured the House committee in January, no approval from Congress was sought for the Iceland operation. Rather, the operation was concealed from Congress. On July 3, Senator Burton Wheeler of Montana publicly revealed the existence of the secret operation for the first time, telling reporters he’d been “reliably informed” that “American troops will embark for Iceland to take over that island.” Wheeler was furiously denounced for the disclosure. On July 8, Early, the White House press secretary, charged that Wheeler had “endangered the lives of American bluejackets and marines by telling the world of the impending occupation of Iceland,” according to the New York Times. Wheeler replied with the statement: “I believe the American people have the right to know every step that is being taken by the Administration which tends to involve us in war.”

Over a year earlier, in May 1940, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had launched “an extensive intelligence operation, including wiretaps, aimed at keeping an eye on the president’s critics, including Wheeler,” according to an article published in 2012 by the Montana Historical Society. Hoover’s operation was carried out “with full White House support.” He sent “personal and confidential” memos to Roosevelt’s staff detailing surveillance not just of Wheeler himself, but his wife and son. The Secretary of War, Stimson, accused Wheeler of engaging in “subversive activities against the United States, if not treason.” On January 15, 1941, in testimony before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Stimson was asked by Congresswoman Edith Rogers of Massachusetts if he thought the enactment of “Lend-Lease” would “eventually lead our country into this war.” Stimson replied, “I do not.”

All of this is 100% true, regardless of whatever beliefs purportedly existed inside Wheeler’s brain at the time. Accordingly, there was absolutely no “lie” pertaining to Wheeler anywhere in my article. The only way to rationally interpret what I wrote as a “lie” would be if one’s objective is to spew psychotic, personal hatred at me.

However, there are some other interesting facts concerning Wheeler that are worth highlighting. In his 1962 memoir, Wheeler wrote: “What I am certain of is that FDR, from whatever motivations, never tried to keep us out of war — while deliberately misleading the people into thinking that he was.” Notably, even those who were pro-interventionists at the time came to agree with Wheeler. While they supported interventionist US policy to draw the country into the war, they nonetheless recognized that the Roosevelt Administration had engaged in concerted deception when it denied that US policy was indeed geared toward bringing the US into the war.

As the Saturday Evening Post editorialized on October 11, 1941:

One year ago it was still unimaginable that this country could become involved in another world war unless or until the Congress declared war in the name of the American people. Yet that has happened. When did it happen? For us it happened with the passage of the Lend-Lease Law, which the Administration represented as a measure to put the war further away, but which was, as we said, a law under which the President, in his own discretion, could conduct undeclared war against Hitler. After that we were unable to support the fiction that the country was not at war. And we were not surprised when the President’s first report to Congress on the operations of the Lend-Lease Law turned out to be an official statement of the Government’s direct participation in the war.

The Saturday Evening Post quoted Herbert Agar, one of the leading members of the “Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies” — an ardently pro-intervention group — who confessed as to the “Lend-Lease” bill: “Our side kept saying in the press and in the Senate that it was a bill to keep America out of war. That is bunk. And I think this failure to say exactly what a thing means is an illustration of why our democratic world is being threatened now.”

Norman Thomas, Burton Wheeler, and the Saturday Evening Post were hardly alone in recognizing that the enactment of “Lend-Lease” had brought about US warfare against Germany. On September 3, 1941, the New York Times editorialized: “The United States is no longer a neutral in this war. It is no longer on the sidelines. It has made its choice. It is a belligerent today... the definitive action was the passage of the Lend-Lease Act.”

If you want to draw a slightly foreboding contemporary parallel, here’s one worth consideration: on September 24, 2022, Sergey Lavrov, the Russian Foreign Minister, alleged at the UN that the US is legally a “direct participant” in the Ukraine war, given — among other reasons — its “direct involvement in the use of lethal weapons.”

“The United States is by no means neutral in this situation and is a party to the conflict,” Lavrov said. This comment by Lavrov is worth taking note of, given that Vladimir Putin has threatened nuclear reprisal in relation to the Ukraine war, and prominent Russian figures like Dmitry Trenin — who was recently head of the Moscow branch of the US-funded Carnegie Endowment for International Peace — have suggested that Russia may launch a nuclear attack against the US.

The aforementioned October 11, 1941 edition of the Saturday Evening Post also reported that for the longtime military affairs editor of the New York Times, Hanson Baldwin, US entry into World War II was officially initiated with “the dispatch of an expeditionary force to Iceland,” because this “meant the beginning of a shooting war.”

Which brings us to another egregious misrepresentation I’m alleged by Katz to have made:

Here is what I wrote in the article:

Roosevelt delayed full implementation of the convoy plans till August, but in the meantime, he declared an “unlimited national emergency” on May 27, and on June 5 secretly ordered the US occupation of Iceland. US forces were to replace British occupation forces that had already been present on the island, under protest from the Icelandic government. According to a study conducted decades later by the Naval War College Review, the decision to occupy Iceland was particularly momentous because it meant Roosevelt had “decisively effected the reversal of a cardinal principle of American foreign policy proclaimed by George Washington in his Farewell Address: avoid entanglement in European affairs.” Roosevelt eventually tried to get around this quandary by announcing he had extended the Western Hemisphere eastward, and that Iceland was now covered by the Monroe Doctrine. To exhibit this new hemispheric adjustment, Roosevelt drew on a map in crayon:

Here is how the Naval War College Review study I cited characterized Roosevelt’s justification for ordering the US occupation of Iceland:

In an act of incredible cartographic finesse, the president also undertook to extend his powers by ‘moving’ Iceland into the Western Hemisphere.

On 11 July Roosevelt showed Hopkins a map he had torn from a National Geographic magazine. On this map Roosevelt drew a line to show his idea of the extent of the Western Hemisphere the US Navy was to defend; Iceland was conspicuously within that area... Finally, all of Roosevelt’s efforts as commander in chief to ‘move’ Iceland into the Western Hemisphere paid off by allowing him to dispatch troops to the Island.

Of course, what both I and the Naval War College author meant by this was that Roosevelt had moved the “Western Hemisphere” eastward for the purposes of delineating the territory over which the US claimed jurisdiction per the Monroe Doctrine. This should’ve been evident to anyone who is minimally fluent in the English language, and actually read what I wrote in my sentence: “Roosevelt eventually tried to get around this quandary by announcing he had extended the Western Hemisphere eastward, and that Iceland was now covered by the Monroe Doctrine.”

A literalistic interpretation of the “Western Hemisphere” as used by Katz — literally everything west of the Prime Meridian — would mean that all of Portugal, nearly all of Spain, nearly all of England, and part of France had “always been in the Western Hemisphere,” and therefore were always considered covered by the prevailing conception of the Monroe Doctrine. Which is ludicrous.

Here is how the US National Archives summarizes the origin of the Monroe Doctrine: “The Monroe Doctrine was articulated in President James Monroe’s seventh annual message to Congress on December 2, 1823. The European powers, according to Monroe, were obligated to respect the Western Hemisphere as the United States’ sphere of interest.” To my knowledge, no one has ever suggested that Monroe was referring to territorial England or France as part of “the United States’ sphere of interest” in his promulgation of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823. Hence the need for Roosevelt to “extend the Western Hemisphere eastward” in 1941 to justify the secret US occupation of Iceland, even as Iceland had always in a literalistic sense laid west of the Prime Meridian.

If you’re somehow going to call this a “lie” on my part, or even some sort of egregious misrepresentation, it’s possible your venomous personal hatred is skewing your perception of reality.

In sum, I’m happy to have demonstrated how spectacularly wrong Katz was on the substance. It seems that Norman Thomas — whom Katz apparently purports to venerate — was prescient when he wrote in the 1951 memoir that Katz cited: “It is not healthy for the future that an honest effort to keep our country out of war should have been so unjustly stigmatized.” I could hardly offer a better description of Katz’s current behavior.

Your patience is remarkable and commendable. Thank you so much for this very interesting follow up.

The excellence of your work on this extremely important issue has made a paid subscription very worthwhile.

Thank you so much, and please keep up the great work.

Such an interesting follow up to a very interesting original article. Forget Katz, let’s do more comparisons to WWII and Ukraine. Would really like to read more on this in the future. I must confess that in all my years very little of this is actually taught or spoken about, particularly from this angle.